In the heart of western Fiji, nestled within a lush eco-lodge surrounded by rainforest and reef, lives Vili — a passionate farmer, environmental steward, and full-time team member at TravelWell Fiji and Rustic Pathways. Over the course of a few weeks, I got to know Vili and the local Fijian staff very well, sharing stories and songs over kava every night. I had the chance to sit down with Vili, not just as a colleague, but as someone whose relationship with nature runs deep through generations of Fijian tradition.

In this conversation, we explore how his identity, ancestry, and intimate connection to the land have shaped the way he sees the world — from climate change to farming, and from traditional knowledge to humanity’s place in nature. Vili’s voice is a reminder that environmental care isn’t only about science or policy, but also about listening: to our ancestors, to the earth, and to ourselves.

Can you tell me more about your family and ancestry? What island or village is your family originally from, and what does that place mean to you?

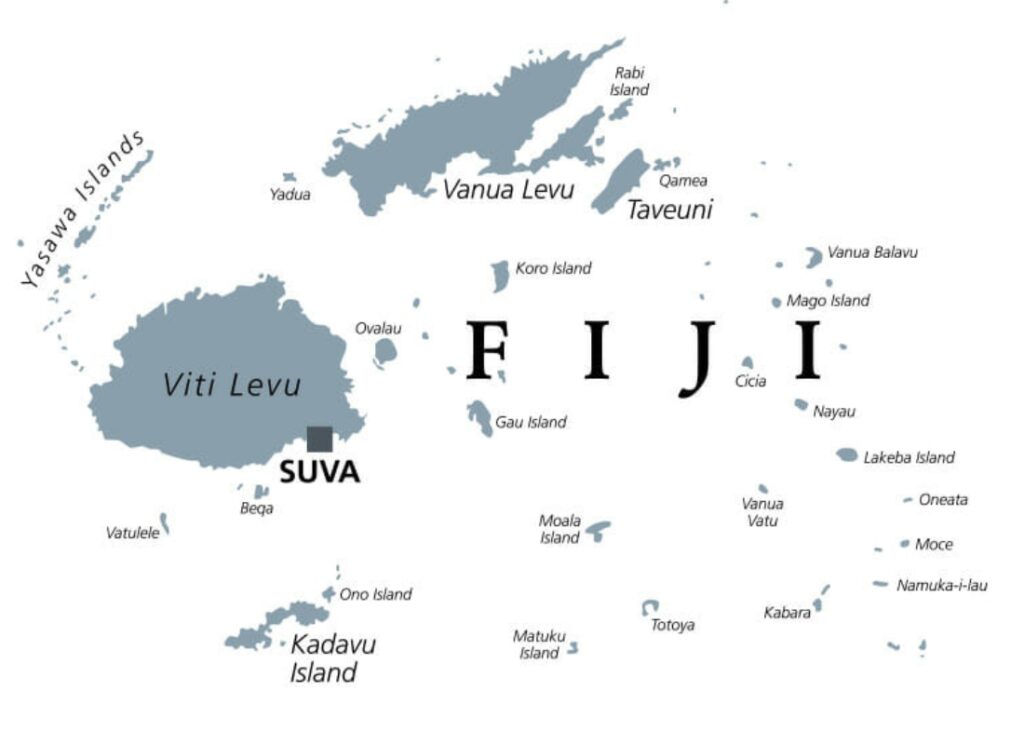

Vili is from Vanua Levu, the second-largest island in Fiji, in a village home to about 500 people. His family originally sailed there from the main island, Viti Levu, roughly a thousand years ago. They had already settled on Viti Levu when the eldest sibling decided he wanted to keep exploring. Back then, they sailed to explore more, particularly at night, using the stars and the Milky Way as their compass.

With the blessing of the village, his great ancestors sent the eldest sibling off with a gift: a plant to be planted once he arrived safely. When he reached Vanua Levu, he did just that—and named the province Bua, which is where Vili’s village is located today.

Vili comes from a big family—he has six siblings and grew up surrounded by cousins. Most of his relatives still live on Vanua Levu, but he left to study on the main island in Fiji’s capital of Suva. He explored a wide range of subjects, from physics to architecture to IT, before eventually settling on his favorite: music. To support himself through university, he worked a ton of jobs—merchandising, forklift driving, music teaching, construction, and even bouncing at nightclubs. In 2017, after finishing school, Vili joined Rustic Pathways and moved from Suva to Momi Bay. He hasn’t looked back since.

The gorgeous Momi Bay base house where I got to know Vili and beautiful Fiji.

Vili has become a very good friend and he can make everyone in a room smile through his infectious laugh. He plays nearly every instrument you can think of: saxophone, trumpet, guitar, ukulele, drums, keyboard—and of course, like every other Fijian, he has a beautiful voice.

The Clans of Viti (Fiji)

In Fiji, there are traditional clans that form the backbone of village life. There are six main ones, each with a specific role in supporting the community and raising future generations. Clans are inherited through paternal lineage, and gender doesn’t matter—there can even be female chiefs. The clans are:

- Chiefs – the leaders and decision-makers of the village.

- Spokespersons – mediators between the chief and the people.

- Priests – advisors to the chief and natural doctors of the village, holding deep knowledge of plants, herbs, and the land.

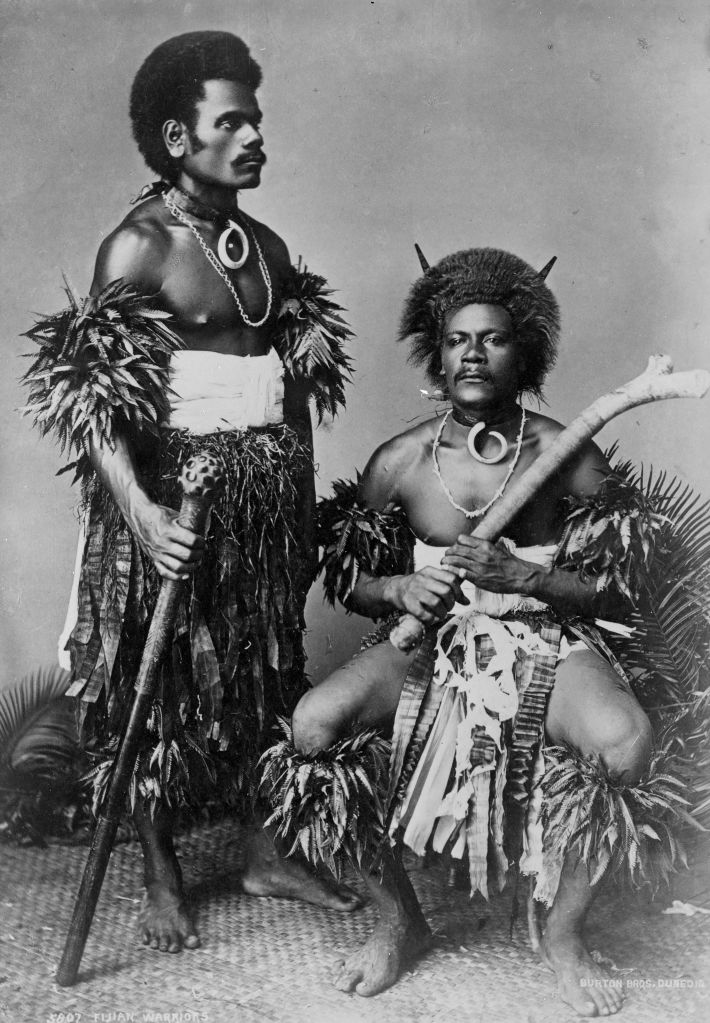

- Warriors – protectors of the people, land, and chief, including personal bodyguards and boundary defenders.

- Builders – responsible for infrastructure and boat-building, inheriting their skills from observing elders. They don’t use Western tools like levels—they measure using the horizon or trees. They are the inventors and engineers.

- Fishermen/Hunters – providers of food using ancient techniques, like using bundled leaves as fishing nets or tracking fish based on passed-down knowledge.

Though Vili’s kind nature might not show it at first glance, he comes from the warrior clan, bati. The warrior role has a fascinating and intense history. During the era of traditional cannibalism, iTaukei Fijians (Indigenous Fijians) believed that a chief’s body held sacred power. If a chief died in war, the opposing side would try to take the body to feast on their bones or drink kava from their remains—hoping to absorb that power. The warriors’ job was to prevent that at all costs and recover the chief’s body.

Clans are still highly respected today, especially during village functions. Vili actually didn’t know his clan until high school, when the village chief passed away and he was called into duty. His uncles were summoned to protect the chief’s body until burial, and Vili learned then that he was also part of the warrior clan.

Initially, Vili’s father didn’t want him to go—at the time, the family was undergoing a religious shift and some viewed traditional rituals as witchcraft. But Vili insisted he needed to fulfill his role. As he sailed back to Vanua Levu with his uncles, he stepped into a sacred rite of passage. The body of the chief must be protected for four days before burial. Leaving behind their Western clothes, the warriors chose their weapons, painted their faces with traditional designs, and stood guard.

Vili remembers being surrounded by fellow warriors—big men with gloves and spears—and realizing how deeply spiritual the experience was. He was shocked to see that, in this context, traditional law overrode government law. “Anything that attempted to cross the barrier would be eliminated,” he explained. The village fell completely silent. For four days and nights, wooden drums beat and conch shells echoed through the still air. No one slept. No one cried.

Vili described this experience as transformational. It felt like he was “stepping into a different kind of power, standing barefoot on the land, grounded, seeing all the elders stepping into the role.” He didn’t feel alone—he felt the presence of his ancestors around him, connecting him to his environment and community in a spiritual sense. “I was there grounded in the physical sense, but the ancestors were protecting in the spiritual.” Even hearing him tell the story gave me chills.

It’s a powerful way to understand how Vili came to be who he is today—how ancestry, place, and tradition have shaped him.

How would you describe your relationship with the environment and nature today? Can you tell me more about Vanua?

Vanua is a word you’ll hear a lot in Fiji. It technically means “land,” but its meaning runs much deeper. Vili explained it as “a saying and belief that the land has eyes.” While other cultures have similar ideas, in Fiji, Vanua refers to an all-encompassing understanding. It includes the land, the people who live on it, and the witnesses—seen and unseen—who observe how the land is treated. It spans past, present, and future, and brings justice to anything that disrespects nature.

“The true meaning is home,” Vili said, “and when you don’t keep your home well, problems arise.”

Vanua is feared and respected more than religion. If a village is out of balance—people mistreating one another, or the land or animals—Vanua will send a sign. Crops will fail, animals will bring destruction, and famine might follow. “There’s not a scientific explanation,” Vili said, “but it happens in a spiritual sense. Vanua reflects the state of the village.” He paused. “Vanua can kill and Vanua can give.”

“The sea is our pathway to each other and to everyone else, the sea is our endless saga, the sea is our most powerful metaphor, the ocean is in us.”

Epeli Hau’ofa, Fijian writer and anthropologist

One example he gave showed the enormous weight that Vanua carries in Fijian culture. In Vili’s village, when a new chief is chosen and goes through their initiation rituals, the final step is to wade into the ocean. If sharks don’t bite, it’s a sign that Vanua accepts them.

I asked Vili how climate change affects this relationship. He reflected on the modern shift away from village life. More Fijians are moving to cities or going abroad, and elders—the holders of traditional knowledge—are often left behind. This disconnect weakens their ability to fight climate change using indigenous practices.

Every iTaukei Fijian family has specific natural elements they are not allowed to harm—a plant they can’t cut, a fish they can’t eat, a bird they can’t hunt. For Vili’s clan, those are the mangrove plant, the shark and halibut, and the green-feathered parrot. These sacred protections are a form of traditional conservation—powerful in their simplicity, yet increasingly forgotten.

“People are losing their knowledge,” he told me, “and with it, their culture and identity.” But these practices—small as they may seem—are major ways Fijians have always cared for the land. And in the face of the climate crisis, they matter more than ever.

What traditional or indigenous knowledge have you learned growing up that continues to guide your relationship with the land and sea?

Vili’s connection to the land and sea has been present since childhood—so deeply woven into his upbringing that it was never something separate or abstract. It was simply life. Raised in a coastal village where the rhythms of nature dictated the pace of each day, Vili grew up with an intuitive understanding of Vanua. His father, known for his green hands, passed down more than just farming techniques; he instilled a way of life rooted in respect, reciprocity, and care for the environment. Together they planted everything from mangroves and root crops to orchids, avocados, and watermelons.

Farm days began before sunrise. By 5am, Vili and his father would leave the house, stopping mid-morning for tea, and continuing on foot or by transport until they reached the farm. They’d tend to the land for hours, harvesting and cleaning crops, before heading back—pausing to dive for clams in freshwater streams or gather edible ferns. These experiences taught Vili to take only what was needed, to waste nothing, and to live in harmony with the natural world. Other days, he’d follow his mother to the ocean as she fished for mussels and prawns, while he gathered coconuts for dinner. These were not occasional lessons—they were the structure of his youth.

Later, while studying in the capital city of Suva, Vili felt the absence of this way of life acutely. He’d often skip class to wade into rivers and fish, seeking that sense of rootedness his body craved. His connection to the land and sea wasn’t a memory; it was in his blood.

What inspired your interest in farming? Has this always been part of your family or something you chose on your own?

Farming has always been part of Vili’s story. It began with watching his father’s “green hands” work magic in the soil—hands that could coax life from anything. But it became his own path in university, when an unconventional opportunity deepened his commitment. While studying in Suva, Vili entered a work-trade agreement with his music professor: he’d farm the professor’s land in exchange for tuition. For three years, he lived simply, built his own house, and grew taro—his first introduction to farming as a livelihood. It was the first time he saw a return from the land beyond sustenance, and it planted the seed of an idea: farming could be more than a tradition—it could be a future.

After joining Rustic Pathways and working at the Momi Bay base house, Vili began growing kava during breaks back home. He sold it at the market, reinvesting the earnings into bigger dreams. Just over a year ago, those dreams took root in the form of a thriving farm at the base house. Alongside his younger brother—who shares their father’s green thumb—Vili helped design a vibrant ecosystem of crops: cabbage, okra, dragonfruit, eggplant, cilantro, pumpkin, bananas, papayas, citrus, herbs, and more. The idea was simple but powerful: grow enough to feed themselves and the students they host, without putting extra strain on the local food systems.

This is true farm-to-table living. Their amazing in-house chef, Sandy, prepares every meal with produce from the land just outside the kitchen—fresh, seasonal, and deeply nourishing. Right now, Vili is focused on watermelon, with plans to grow maize for the summer. The next chapter? A production space where they can dry cassava into flour, turn maize into cornmeal, and create sustainable food for themselves and their broader community. They’re using permaculture principles to ensure the plants support one another—and their long-term vision includes donation-based systems to expand food access beyond their own team.

As someone who has eaten three meals a day straight from this land, I can confidently say: it’s not just farming. It’s soul work.

For those who feel disconnected from their ancestral land or from nature in general, what wisdom would you want to share? Where can someone begin to rebuild that relationship?

I actually had a long conversation with Vili while I was living at the Fijian base house about this very topic—on a deeply personal level. I remember feeling a twinge of jealousy watching how connected all my local friends seemed to be with their environment, while I often found myself chasing that same feeling. So I asked Vili how someone like me, or anyone feeling disconnected, might begin to rebuild that relationship with the natural world.

He told me a story from his own life, about the years he lived in the capital city of Suva. Even though he grew up deeply rooted in his village, surrounded by land and sea, moving to the city triggered a sense of disconnection. Nature felt distant. But he found his way back—through the river. Almost every day, he would go fishing. It became a ritual that anchored him, a way to return to himself. He also stayed in touch with loved ones through phone calls and technology, keeping those threads of community alive.

Vili explained that in Fijian belief, we are not separate from nature—we are nature. We belong to it, and it to us. As we spoke over the phone, birds sang in the background of the call, a reminder of this ever-present connection. “Everyone is busy,” he acknowledged, “but taking the time to ground yourself is important.” His simplest piece of advice? Take your shoes off. Wherever you are—city, suburb, or countryside—if you can find even a small patch of grass or earth, go there. Walk barefoot. Feel the ground beneath you. Sit still. Listen to the birds. Breathe. And if you’re able, he encourages taking a small trip into a more natural place. It’s always worth it.

When I told him about my fears of feeling disconnected from my ancestral roots, he reassured me: “You are your ancestors.” That stayed with me. “You have all their genes—you are a walking lineage of people who came before you, walking the same earth they did.” Even if we’re living in places far from where our ancestors once lived, Vili reminded me that there’s beauty in that. Fijians, too, traveled far from their origins—to Fiji, to Australia, to the US. “We are still doing what our ancestors did: journeying, crossing oceans, exploring new lands.” In that sense, we are honoring them with our lives. And while we may not have the same knowledge they did, we can still access the same feeling—of belonging, of connection—through nature.

“Nature will always be our connector,” he said. Because we are just animals, too. “Everyone is part of the land, like Vanua. Everyone is connected through our ancestors—it’s never just you alone.”

Vili hopes no one feels disconnected, and that we all find grounding in remembering who we are and how far we’ve come. “It’s a beautiful thing—continuing our ancestors’ legacy, thriving in the natural environment, and adapting as it changes.” Even if it’s just five minutes a day, he says, give yourself space to invite that connection in. Vanua—connection to land, people, and spirit—is always accessible.

One of the most powerful things he told me: “Nature is always calling.” In Fiji, there’s an ongoing dialogue with the environment. If you want to know whether the tide is high or low, you listen for the bird who calls it. Everything in nature has a purpose. This wisdom has been passed down for generations, and Vili emphasized how vital it is to continue teaching it. Without sharing this knowledge, future generations may never know it—and lose that sacred connection.

He believes the climate is trying to send us a message. But we have to be willing to listen. “We should expect natural disasters,” he says, “because we’re not giving attention to what really matters—protecting natural resources.” Not because it’s ‘right,’ but because that’s what we’re meant to do as humans living on this earth.

My takeaways from all of this?

Vili and the entire TravelWell Fiji & Rustic Pathways team shared so much wisdom, culture, and love for their environment. Their connection to each other and the land is something you feel immediately when you’re there. Over Kava circles and early breakfasts, I learned more than I ever expected—about Vanua, about simplicity, about what it means to belong to a place.

As someone still seeking that deeper connection to nature, learning from the Fijian perspective truly shifted something inside me. It made the whole concept feel less daunting and more intuitive. In the end, it isn’t about doing everything perfectly. It’s about presence, about listening, and about remembering that the land has always been calling—we just need to answer.

A glimpse into an unforgettable few weeks with the TravelWell Fiji team — featuring Vili, my amazing co-leaders Knox and John, and our manager Jerry.❤️❤️❤️